The drive west from Portage to Spring Green, Wisconsin takes about an hour and a quarter, and on Wednesday the 26th, the louring skies made the passing fields look preternaturally green.

At noon I reached the Spring Valley Inn, first designed in the early 1990’s by the Taliesin and Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation as a visitor’s center and later purchased by the current owners, John and Patricia Rasmussen, who along with Charles Montooth, apprentice to Wright and member of the Taliesin Associated Architects, turned that visitor’s center into the Inn’s handsome reception area and lounge, constructed the extant 35-room hotel, and in 1994 adding a capacious indoor pool and conference room. All the furniture and appointments were designed by Taliesin architect James Pfefferkorn and built by local Master Craftsman Rick Kraemer. For Wright aficionados, this is certainly the RIGHT place to be.

After a quick look around, I used the time before check-in to scout out the nearby House on the Rock Resort where we were to have dinner and to locate both the American Players Theatre (APT) and nearby Taliesin East.

That accomplished, I had a fine lunch at the General Store just off the railroad tracks in Spring Green, a tiny town of some 1500 (even smaller than Madbury’s 1900) where the fire station, bank, and at least one private home were clearly under the FLW influence.

Once friends Charlotte and Ed arrived at the Inn, we went off to an early dinner at the House on the Rock Resort,

and then on to a production of Our Town at the APT’s outdoor Hill Theatre.

Charlotte had never seen Thornton Wilder’s play, and while we all thought this production quite fine, I regret it didn’t come close to the devastating David Cromer production I saw in the 199-seat Barrow Street Theatre in 2009. In fact, even this clip of that show (http://www.barrowstreettheatre.com/about-us/past-productions/our-town) I found online just a few minutes ago still brings tears to my eyes. As my late UNH theatre colleague John Edwards once pointed out, theatre space is everything, and in fact, when I later took my husband David to see the Cromer production then playing in Boston, it did not have the same effect on me or the audience. That night in the West Village just off Washington Square may be the single most powerful performance of anything I have ever seen. With the house lights up throughout, David Cromer, who both directed and played the Stage Manager, was like the rest of the cast within easy reach of the audience; there was no hiding anyone’s emotion on stage or off. The young woman sitting in front of me, seemingly on a date with her equally young escort, was embarrassed by her so-visible tears at the end of act two’s wedding, and no one made it dry-eyed through the final act and Emily’s epiphany inspired by revisiting a single seemingly unimportant morning past, its precious evanescence recaptured and for once observed in perspective by Emily and audience alike. In that production, staged as scripted with minimal set, props, and mimed actions, the curtains at the back of the thrust stage suddenly revealed behind a hitherto unseen proscenium arch a kitchen scene utterly realistically realized by period costumes, lighting, and box set complete with working stove and real bacon sizzling and scenting the theatre air: a real coup de théâtre. Just remembering that darling boy playing Emily’s young brother Wally, dead of an appendix burst on a camping trip, wearing his Boy Scout uniform, sitting in his chair/grave among the dead, moves me to tears even now. No re-living that moment, I guess.

Even so, I think it a better play than my friends do, and we had a jolly argument about its themes the next morning at breakfast, all of us grumpy from a less than satisfying sleep. How delightful to disagree without rancor among dear friends! Charlotte’s objections forced me to formulate a defense of the script I’d never before thought through: the conversational dialectic at work as it should be. How I wish political divides could be similarly enlightening!

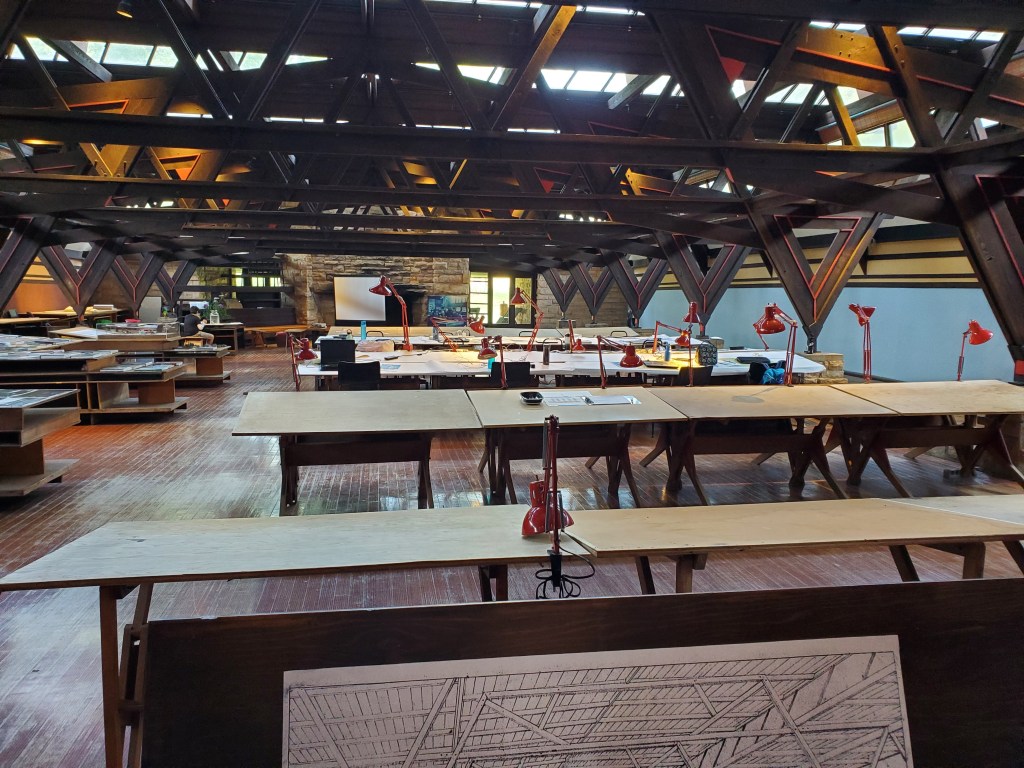

After breakfast we headed out to Taliesin East for a two-hour tour led by a very well-informed and appealing docent, Ben, a Wisconsin-born farm boy (he reported he’d done his share of tasseling the corn crop) transplanted to NYC. A shuttle bus drove us around the Taliesin property, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and Ben led us through both the Hillside Studio and Taliesin itself.

The tour group was a singularly knowledgeable one, too, which was great: one young woman was clearly a Wright scholar, and another older woman was coincidentally not only from New Hampshire, but a docent at the Zimmerman home, one of Wright’s Usonian houses now owned by the Currier Museum in Manchester.

I’d prepared for the tour by reading T. Coraghessan Boyle’s historical novel The Women about the four most important women in FLW’s life, his three wives—Catherine (Kitty) Tobin, Maude Miriam Noel, and Olgivanna Lazovich Milanoff—and his mistress, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, infamously murdered at Taliesin along with her children and four others when servant Julian Carlton set the place on fire in 1914 and dispatched its occupants with an ax as they fled the burning structure. The rest of my knowledge of FLW came by way of my late husband, architectural historian David Andrew, an authority on FLW’s first employer, the equally renowned Louis “form follows function” Sullivan. So, this tour was both of great interest to me and somewhat haunted.

My conclusion: FLW was indeed a talented visionary, as well as a supreme narcissist; standing only 5’6,” the architect placed many ceilings at Taliesin at so low an elevation that even I (5’8”) felt compelled to stoop. My David always said “his mother loved him,” and that set him up to believe himself a Great Man well before he established for himself such a reputation. “Early in life,” he said, “I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility. I chose the former and have seen no reason to change.”

David and I once spent the night in upstate New York’s 19th-century experimental utopian community, Oneida, where John Humphrey Noyes (1811-1886) and his followers pursued his radical notions of perfectionism, including free love, then regarded with the same suspicion and disdain the local Spring Green populace later felt for the adulterous relationship of Mamah Cheney (1869-1914) and Frank Lloyd Wright (1967-1959). The structures we saw on the tour dated from 1902, 1911, 1932, and 1952, so my experience of Taliesin and Boyle’s well-researched novel together brought to mind not only Oneida and the social experiments of the early twentieth-century, but also the 1960’s and our own current culture wars. Historical perspective: another perk of travel.

After a refreshing swim in the Inn’s lovely pool while my friends explored Spring Green’s amenities, we all returned to the American Players Theatre with a pre-performance picnic (from Wander Provisions in Spring Green) to enjoy on theatre grounds amply furnished with sheltered picnic tables and piped-in classical music.

The Merry Wives of Windsor, one Shakespeare play I’d never seen played (and, frankly, didn’t think much of) was brilliantly, hilariously produced. How the actors in their elaborate costumes (Falstaff in a fat suit, no doubt) kept from fainting as they bustled about in the 93o heat, I can’t imagine, but the play was fantastic, rollicking fun: just the ticket after the beautiful, sober modernity of Taliesin.

Next morning my friends headed back to Iowa City and I drove east to Milwaukee, with a brief stop in Madison to visit the U of Wisconsin’s fine Chazen art museum and remark on the symbolic layout alumnus Ed had made clear to me: The Capitol on unimpeded axis with the central University campus: learning and government on equal footing. Would that balancing act still obtained across our nation.

A big storm arrived at my airport Hyatt shortly after I’d cozily settled in there, and the next morning my flight took off right on time, delivered me to Orlando for a layover long enough to have a leisurely dinner and finish the Boyle novel before finally arriving back in Manchester around 1 am Sunday morning.

As I finally climbed gratefully into my own Madbury bed, I thought how fortunate my travels had been, and how lucky I am to have such family and friends. As always after a journey away, I recognized that truly there’s no place like home.

Leave a reply to Claudia Champagne Cancel reply