7 September 2023

Labor Day may mark the unofficial end of summer, but the weather in New Hampshire today begs to differ: the actual temperature outside is 90o, the heat index 99o, and here in my un-air-conditioned study it is 86o. My sister Jane in Florida and I have been texting back and forth, recalling and wondering at our ability to survive our public school education in St. Petersburg in schools with no ac. I recall the unnatural contortions of my right arm as I struggled to find a way to keep my sweating hand off the test paper I was trying to complete, and the exquisite joy of being allowed at recess to buy a 10¢ waxed paper carton of thirst-slaking, ice-cold orange juice from a hall vending machine. Many schools in New England are still not air-conditioned, and in this “heat emergency,” some have closed for the rest of this week. In Jane’s and my day, we hoped for hurricanes to delay the start of school, and fairly often got our wish. Perspectives change with responsibility and property; I’m very grateful Hurricane Idalia missed Jane there in Safety Harbor, and hope Hurricane Lee still brewing in the Atlantic will keep its distance.

Despite my status as a retiree, I did my best to substitute pleasure for workaday chores over the holiday weekend, discovering that Lexie’s at the Great Bay Marina (with excellent fish tacos) is staying open on weekends through September this year—a perk of climate change?

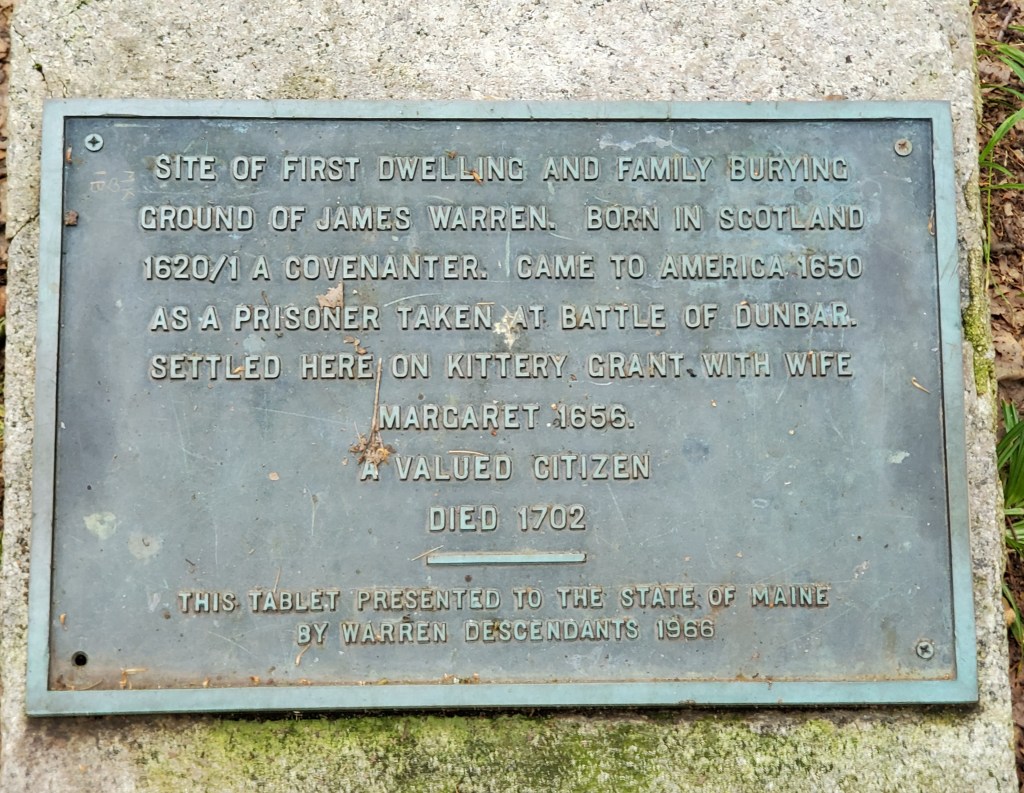

And I was pleased to find I could still hike from shipping merchant Jonathan Hamilton’s striking Georgian mansion (c. 1785) picturesquely sited on a bluff overlooking the Salmon Falls River into Vaughn Woods State Park, navigate the ups and downs and trip-threatening roots of the River Run trail, and return on the more level bridle path to a perch in the Hamilton House garden where I caught the cooling breeze from the river below. Most gratifying.

Even with such holiday embellishments, I still managed to get a few things accomplished at home: the deck railing is now once again shining with the penetrating oil that should protect it through the coming winter; the Behr brand I once had to smuggle in from Canada is now once again available at Home Depot, illustrating the vicissitudes of earlier environmental regulations.

And I managed to get all the mowing done without again suffering the consequences of disturbing a cicada killer wasp nest that I’d earlier mistaken for a more harmless groundhog excavation. I do like mowing, especially since switching to a quiet, lightweight, electric machine that doesn’t turn gas into stink and noise: the benefits are good exercise, money saved, a sense of accomplishment, and a chance to commune with my late father George, who did all the sweaty work of maintaining the lawn and landscaping of the Murphy home in St. Pete.

Best of all, I finished Anthony Doerr’s hefty 2021 novel, Cloud Cuckoo Land, a paean to texts and those who preserve them.

Initially challenged by the fragmented narrative weaving together lives lived in the 15th, mid-20th, early 21st, and mid-22th centuries, I was nevertheless drawn into following with increasing urgency the seemingly unrelated breadcrumbs finally integrated into a central action: the compulsion of such very different souls alive in such very different times to preserve an ancient but timeless story. Dedicated by Doerr “to librarians then, now, and to come,” the novel

“is an epic of the quietest kind, whispering across 600 years in a voice no louder than a librarian’s. It is a book about books, a story about stories. It is tragedy and comedy and myth and fable and a warning and a comfort all at the same time. It says, Life is hard. Everyone believes the world is ending all the time. But so far, all of them have been wrong.

It says that if stories can survive, maybe we can, too.”

(Jason Sheehan, NPR book review, 28 September 2021)

Given the state of textual expurgation in my home state of Florida (censoring Romeo & Juliet??! Jesus, Mary, and Joseph!), the words of Licinius, the eldest of Doerr’s characters, a dying Greek tutor to rich children in Constantinople, take on new resonance:

“A text—a book—is a resting place for the memories of people who have lived before. A way for the memory to stay fixed after the soul has traveled on.”

His eyes open very widely then, as though he peers into a great darkness.

“But books, like people, die. They die in fires or floods or in the mouths of worms or at the whims of tyrants. If they are not safe-guarded, they go out of the world. And when a book goes out of the world, the memory dies a second death.” (Cloud Cuckoo Land, 51)

Have we in our current fit of “alternative facts” and ignorant censorship entered “a great darkness”? Certainly the daily news suggests the answer is yes. But then, there’s this:

“Sometimes the things we think are lost are only hidden, waiting to be discovered.” (408, 474).

So here’s to those who labor to discover and preserve. As the heroic character Zeno Ninis, once a midwestern POW in Korea captured along with English classicist Rex, remembers:

“Of all the mad things we humans do, Rex once told him, there might be nothing more humbling, or more noble, than trying to translate the dead languages. We don’t know how the old Greeks sounded when they spoke; we can scarcely map their words onto ours; from the very start, we’re doomed to fail. But in the attempt, Rex said, in trying to drag something across the river from the murk of history into our time, into our language: that was, he said, the best kind of fool’s errand.” (462)

Leave a comment