Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman for MurphyMade

Terrestrial icebergs line my Madbury driveway this last day of 2022, plow- and weather-sculpted remnants of the one seasonal snowfall we had before the high winds and warm rain of Winter Storm Elliott’s bomb cyclone melted all the other snow and ushered in this dull, overcast, 53o last day of 2022.

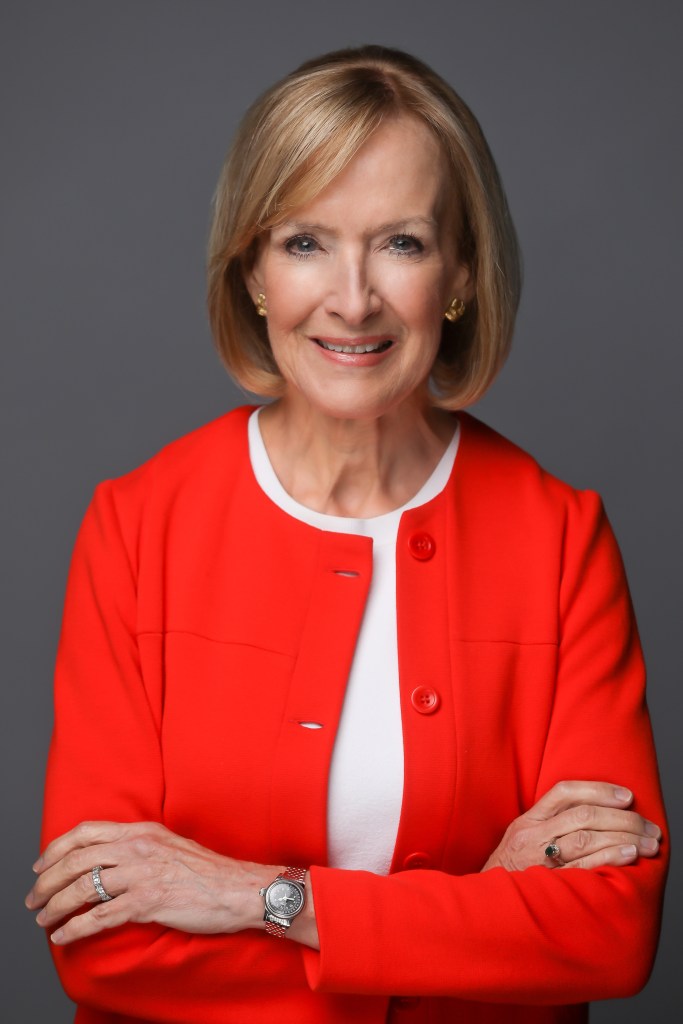

Last days always seem as significant as first days, and the year’s end brings no shortage of opinion synthesizing events of the past year. Today I’m certainly thinking of endings—Judy Woodruff has made her final appearance as anchor of the PBS Evening News. Barbara Walters and Pope Benedict XVI now belong to the ages. Trump’s tax returns are at last public. The House Select Committee on January 6 has concluded its work and presented its recommendations, leaving me an unlikely fan of Liz Cheney, and Putin’s war on Ukraine grinds on as the comedian turned wartime president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a latter-day Churchill, heroically, fearlessly leads his devastated country and is named Time’s Person of the Year, reminding our demoralized democracy of what we used to—and still might again—believe.

Photo © Tony Powell. PBS NewsHour Portraits. September 12, 2018

My run-up to the holidays has included two completely absorbing productions, one theatrical, one choral; Mohs surgery that has rid me of melanoma (yay!) and, at least for now, disfigured my visage (boo!); and trying to make sense both of all that’s past and all that lies ahead. I’ve been observing my annual ritual of the calendar, transcribing into my 2023 (??!!) Letts pocket diary significant happenings from previous years, most often to the accompaniment of whatever’s on NPR. As chance would have it, what I heard on Shankar Vedantam’s Hidden Brain series was an episode about rituals, why we have them, of what use they are, and the empirical research validating them (the episode’s title suggests) as “An Ancient Solution to Modern Problems.” In this broadcast, UConn’s anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas explains the research most recently published in his 2022 book, Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living, offering me a timely epiphany about my own responses to the play and the choral performance that so impressed me in Cambridge and Newburyport within the last fortnight.

A summary of Xygalatas’s findings as elicited by Vedantam:

- The paradox: People often claim that the ritual they perform is the most important thing they do, but they can’t say why.

- Rituals and ceremonial activities unify members of a group into a single organism, not only sharing focus but even synchronizing heart rates among the participants.

- Rituals “hack into our inner world,” helping us cope with anxiety and grief precisely because they are performed together.

- Our physical brains evolved to recognize the necessity of cooperation and membership in a group, but our brains have not yet evolved to address modern problems. Stress as a response to fleeing a tiger is good, but our stressors are not tigers. Our environment has changed, but not our brains.

- Vedantam’s analogy: rituals are like a software patch that bridges this gap for our computer-like, predictive brains.

- When we cannot be certain of what an outcome will be, ritual helps because we CAN control the ritual, which is always repetitive, rigid (always done the same way), and redundant (that is, going beyond what the situation actually requires; the “causal opacity” of the ritual—the fact that repeated actions of a ritual are seemingly unrelated to the goal or outcome sought–is part of their salutary effect).

- In clinical studies, inducing anxiety produces ritualized behavior, a “mental technology” that demonstrably enhances performance.

- Doing things in synchrony with others makes us feel more similar, elevates endorphins, and enhances trust. Think of how many rituals involved dancing and singing.

- “High arousal” rituals—rituals that appeal to ALL the senses, performed collectively–make us feel like brothers, and add to the authority of the one leading the ritual.

- Rituals transform the everyday into the symbolic.

- Participation in a ritual propels the individual into a flow state, lifting a cloud of distraction and inducing a focusing jolt of exhilaration that allows for the impossible (like walking on hot coals without being burned) and extends long past the ritual action.

Although Xygalatas and Vedantam did not make the specific connection to the performing arts, this research into ritual went a long way to explaining the extraordinary effect on me of two performances I attended in the week leading up to Christmas. Of course the Western theatre traditions I taught for decades began in religious ritual—twice, first in Greece’s theatre festivals honoring Dionysus, and again in the Christian liturgical tropes of the early 10th century. The complete engagement of audience and performers when a theatrical piece is really working is an exhilarating drug—a “high arousal ritual” in Xygalatas’s phrase—that dispels all distractions and distills focus in performer and audience alike.

And that’s what I experienced, but had been attributing to the coincidence of two narratives, each capable of moving by words alone, transformed into affecting performance pieces, one by adding music and live performance eliciting both grief and joy, and the other with the full monty of theatrical effects that periodically astonished me into leaving my COVID-masked, surgically compromised jaw agape. First came A Christmas Carol, the so-familiar tale abridged and edited by choral group Skylark’s Matthew Guard from Dickens’s 30,000 words to 5,000, then woven by composer Benedict Sheehan, who with Guard selected, re-arranged, and re-imagined traditional carols, including many unfamiliar ones and folksongs, into a continuous “story score” with incidental music Sheehan composed that with few exceptions accompanied Dickens’s narrative, spoken with measured precision by storyteller Sarah Walker.

The result, performed in Newburyport’s Belleville Church on Saturday, 17 December 2022, was spellbinding and at times heart-breaking. The mezzo soprano’s lament portraying Mrs. Cratchit’s grief at the loss of Tiny Tim, that excruciatingly sad scene the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come offers Ebenezer Scrooge, did in fact elicit tears, making Scrooge’s giddy conversion to humanity all the more joyful at the story’s end. Matthew Guard did a thorough pre-concert exposition of how this sublime transformation of story to Skylark’s now signature “story concert” happened, the work of 19 consummate artists collaborating. Informative and fascinating, that. But it’s the salutary benefits of ritual I now realize that explain for me what this group—and we in the audience—finally experienced.

Ditto Lolita Chakrabarti’s adaptation of Yann Martel’s novel, Life of Pi, into the stage play currently appearing at the A.R.T. in Cambridge, directed by Max Webster in collaboration with scenic and costume designer Tim Hatley, puppetry and movement direction by Finn Caldwell, in tandem with puppet design by Caldwell and Nick Barnes.

Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman for MurphyMade

Anyone who saw Ang Lee’s 2012 film version of Martel’s novel has to be curious about how so fantastic a narrative could be transposed for the theatre. Well, having seen the resulting production, which in April 2022 won five Olivier Awards at London’s Royal Albert Hall, including Best New Play, Best Scenic and Lighting Design, and the Best Supporting Actor Award shared by the seven puppeteers who play the tiger “Richard Parker,” I found my expectations quite marvelously exceeded.

Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman for MurphyMade

A story finally about the transformative power of the story brought home to me how powerful theatrical ritual is, and the afterglow of exhilaration and community lasted long past the long, dark, detouring drive back to Madbury from Cambridge. This extraordinary show stays in Cambridge till the end of January 2023 and heads to Broadway in March, so no further spoilers here.

Takeaways re tigers and tales turned ritual: narrative re-imagined as theatrical performance certainly owes its power to the artful synaesthesia converting words to sensual experience, but the real clout comes from the purposeful assembly essential to ritual, in which the whole community participates—and at least for a while, bonds and heals. I will take that lesson with me into the new year.

Happy 2023!

Leave a comment