Recent days have been unusually crowded with incident, all of it good, beginning on Friday, 2 December with a visit to the Portland Museum of Art (PMA) accompanied by three artist friends, Julee, Shiao-Ping, and Brian, and continuing in good company ever since: serving tea to Jennifer and Linda on Saturday; dinner to Vicky on Sunday; visiting Alnoba’s sculpture park with Phyllis, Cathy, and Jennifer on Monday; enjoying a fireside glass of wine with musicians Mathilde and Edward on Tuesday; taking in the grotesque pleasures of Mark Mylod’s satirical film The Menu on Wednesday; and meeting fellow Madbury Friends of the Library (including two other English majors!) on Thursday. Having now also enjoyed my weekly Friday check-in with Greensboro friend, Cameron, I’m reviewing the many novel connections of the week past, inspired by juxtaposed art and friends, and still rather stunned by all this good company after the isolation imposed by coincident widowhood, COVID sequestering, and retirement.

The PMA, it turns out, is free late Friday afternoons, and is even better visited in the company of three artists, two painters and a photographer.

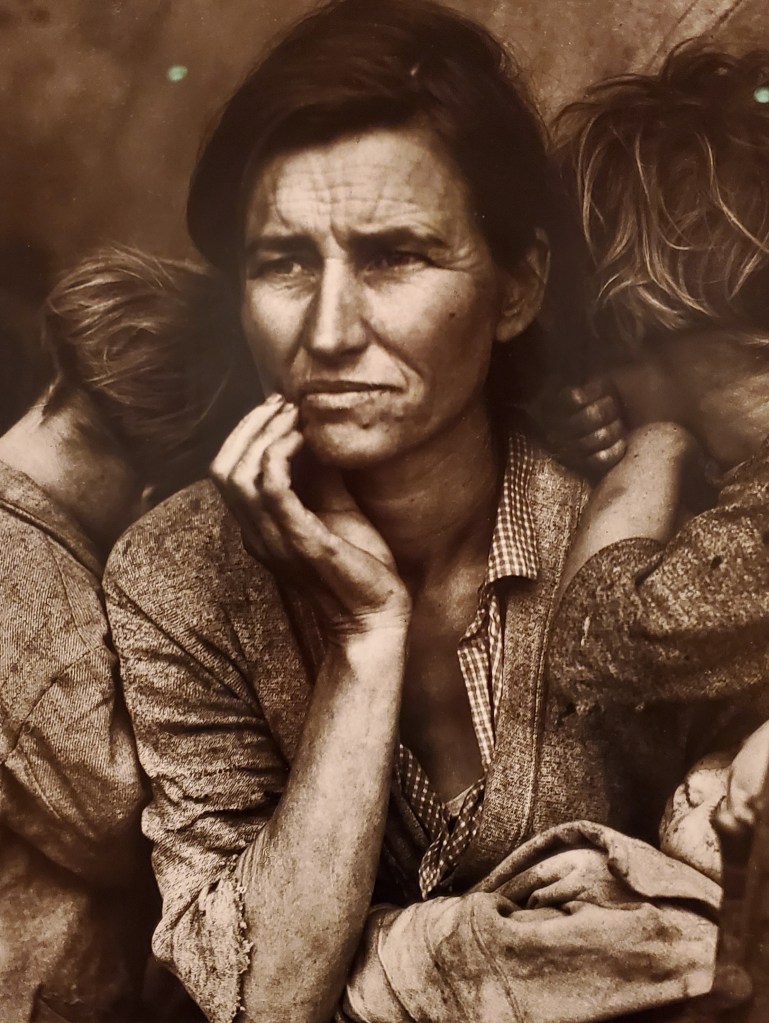

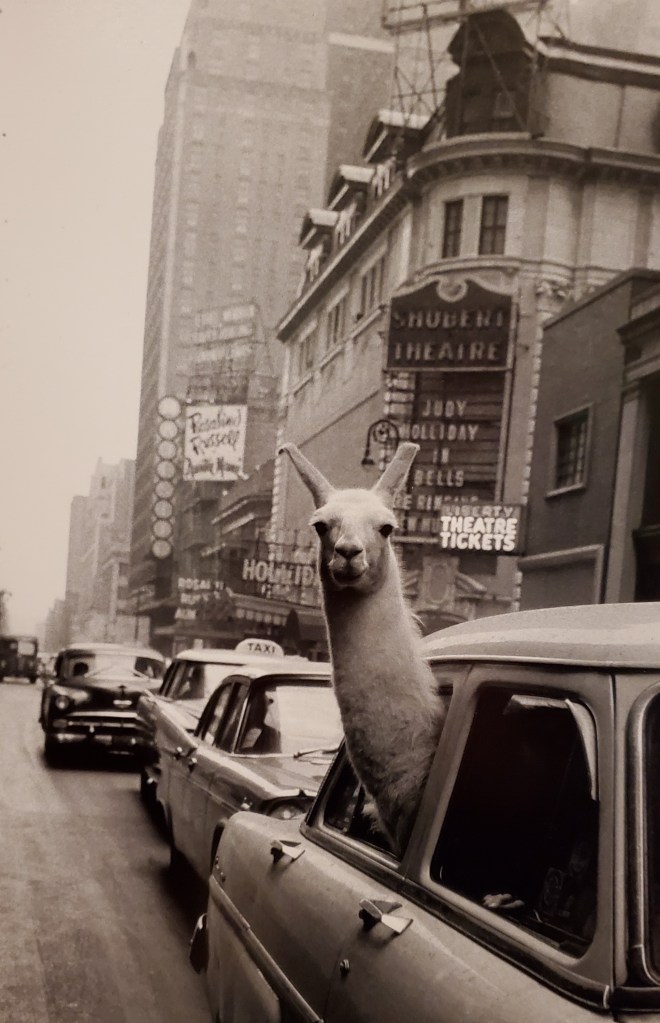

The current big show is the extraordinary bequest of Judy Glickman Lauder, whose photography collection is one gangbuster image after another. From Dorothea Lange’s iconic Migrant Mother, to the painfully moving shot of hope in an old woman’s face as she looks up to RFK, to the whimsical juxtaposition of a llama riding in a car through Times Square, this show fascinates—and suggests, as Brian pointed out, the clarity of an earlier era’s vision, devoid of the ambiguity and irony more currently prized.

We got to talking about how the art scene has evolved, at times distorted into something so far out, so intellectual, and so precious, requiring so much contextual glossing as to invite laughter from both the uninitiated and the skeptical. Such pretentiousness was totally absent from “Presence,” this Lauder collection currently on view.

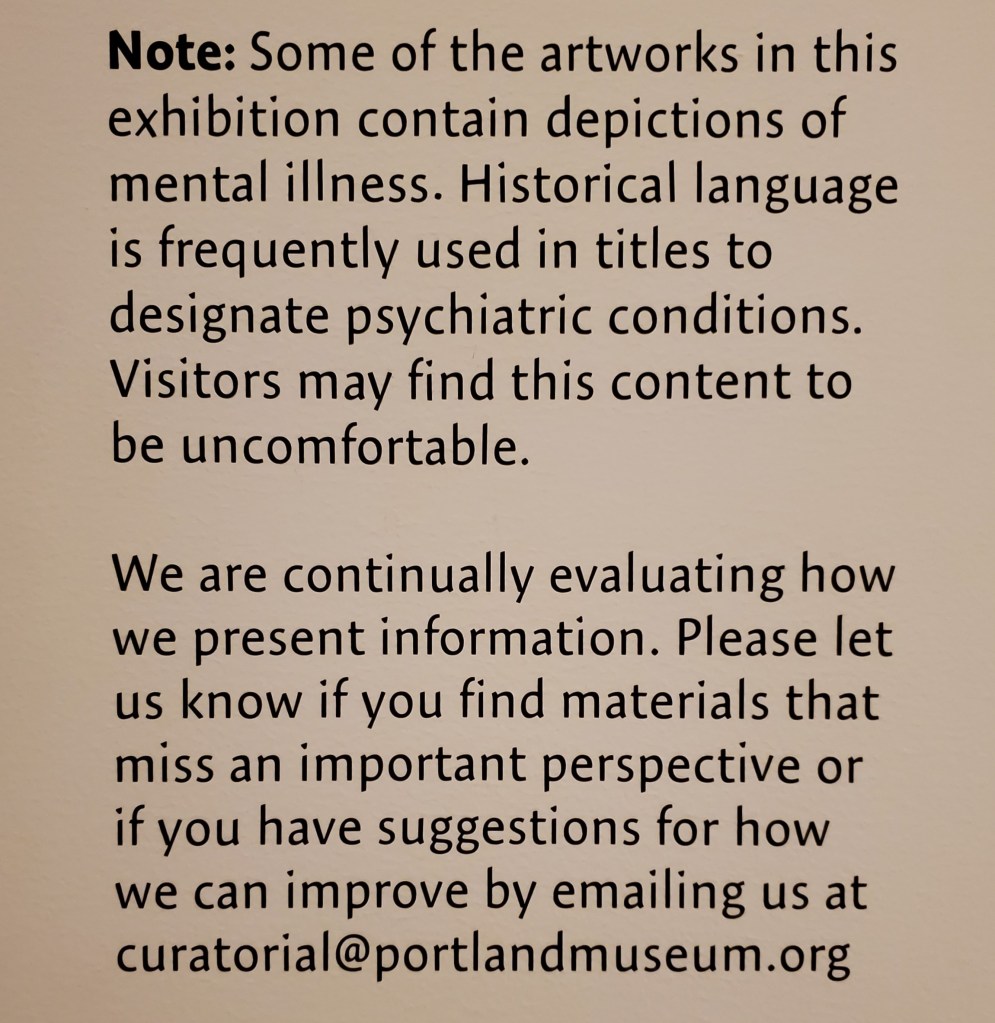

Brian’s assessment seemed to me spot on, and so did his recommending The Menu, a film he thinks nails such absurd affectation (a paraphrase of Brian on The Menu: “You could substitute ‘art’ for ‘cuisine’ in that film and the satire would still apply”). He made me suddenly aware of accommodations, both good and ridiculous, that the modern museum must make. One of the good ones: PMA’s juxtaposing a tidal marsh painting by Hudson River school artist Martin Johnson Heade with a display case of exquisite Native American baskets, linked by a label inviting the viewer to consider simultaneously both Heade’s and the anonymous basket weaver’s vastly different perspectives on sawgrass.

Perhaps a less successful accommodation: the trigger warning message the PMA thought necessary to post to protect patrons’ delicate sensibilities.

Portland’s Congress Street was bustling with artisans hawking their wares as we strolled through the early dark illuminated by Christmas lights to dinner on Monument Square. Such fun.

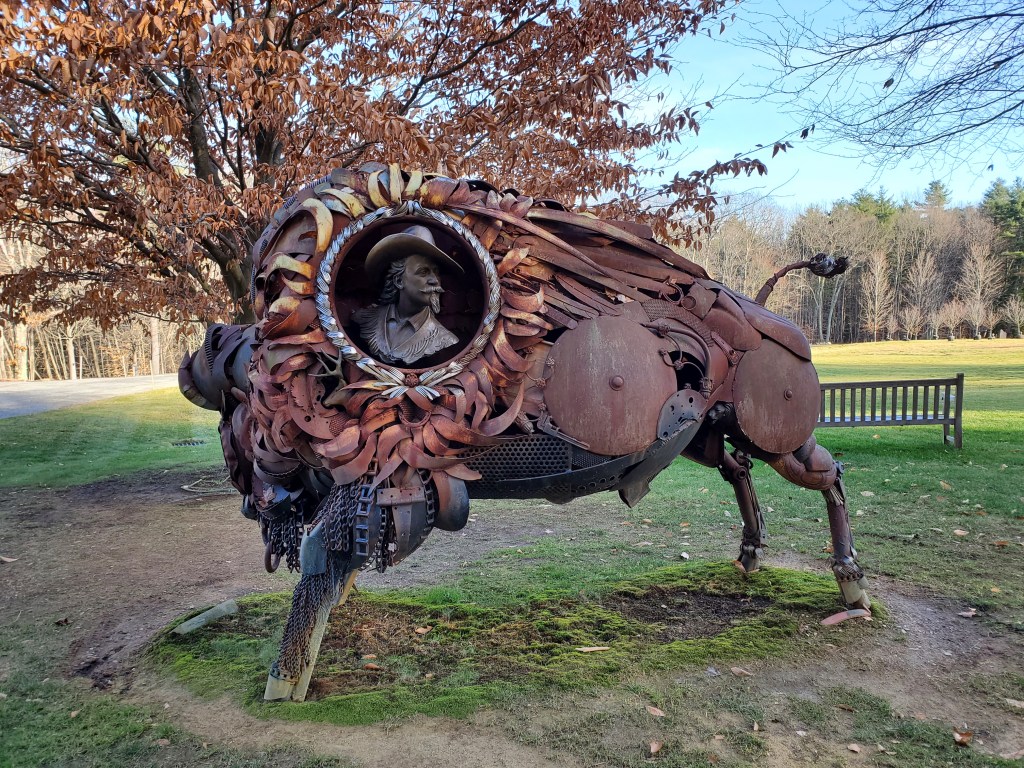

Still under the spell of those PMA images, I went on Monday for a stroll (by invitation only) through the woodlands of Alnoba in Kensington NH, “a destination for retreats, leadership, and wellness” conference center with a remarkable collection of sculptures placed throughout the property. This was my first two hours of negotiating a trail covered by slippery leaves since breaking my ankle at the end of October, but hiking stick in hand, this proved do-able, and the works were intriguing—especially the ones that invite you inside them.

“Alnoba” is an endonym of the Abenaki tribe, their name for themselves in their own language, originally meaning “person,” but post colonization meaning specifically Native American. It’s a lovely word, those open vowels conjuring noblility, respect, and concern for the earth—at least to us, the colonizers who’ve appropriated the word. On reflection, I feel some discomfort in the association of Abenaki identify with high end corporate retreats complete with a ropes course and seminars in “wellness.” But the place and the art are wonderful, no disrespect intended. Here again is the problematic cultural moment that surfaced in the Portland Museum—easily got past in good company with lobster salad for refreshment and sculpture inviting consideration, both of which were in plentiful supply.

The next evening I spent a delightful couple of hours fireside with a nice old vines Zinfandel and two young and very accomplished musicians, Mathilde, who had earlier graced my 70th birthday with such a winning recital, and her husband Edward, who on that same October day was playing cello with Yo-Yo Ma at a Richmond VA concert. We got to talking about how the music world may be the last bastion of memorization, a skill so readily dismissed in recent years that I regularly taught students who thought it impossible that 18th century actors could know the long, formal speeches of neoclassical texts by heart. Mathilde was justly proud of convincing an older piano student of hers to memorize a substantial and difficult piece, and I (quite unoriginally) credited Abraham Lincoln’s extraordinary rhetorical skill with his having much of the King James Bible and Shakespeare by heart, informing his choices and making his words worthy of being inscribed in marble for future generations (and visitors from other galaxies, like Klatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still) to read and admire. Actually, the Lincoln Memorial in D.C. gives new meaning to the “memory palace,” the method of loci, a mnemonic device adopted in ancient Greek and Roman rhetorical treatises. I confessed to using it when I gave my brief birthday speech in our library: each bookcase under my gaze was a prompt to a different segment of my talk. In the case of the Lincoln Memorial, the architecture literally has Lincoln’s writing on the walls.

So. In summary: I’m FOR memorization, sharing art with friends and talking about it, and against the excesses of political correctness and préciosité. The best art—like an extraordinary massage, which thanks to my wonderful neighbor Anne, who is currently learning that particular art with me recruited as an eager practice client—takes you OUT of yourself, affording you ecstasy in the literal sense of that word, removing your mind or body or both from their usual place of function. Such total involvement with an object of interest is not an ordinary experience, and you return from that journey changed in some fundamental way. Just as memorizing literally changes your brain, so does that extraordinary engagement with something outside the self. Such a tonic vacation from ego, that.

But! Art so refined and intellectualized and inaccessible to all but the pampered elite, art all too often prized by them only as status symbol or financial investment, has lost its way. And that’s the point of director Mark Mylod’s delicious black comedy/thriller satire of haute cuisine, The Menu.

Seeing that film after my week of art and wonderful conversations about art meant I was really ready to be entertained and enlightened. And I was! A perfectly conceived and acted allegory of art gone wrong, The Menu is a very stylish and satisfying Gilligan’s Island of reprehensible cultural stereotypes and artists driven mad in service to them. Only one character, there by chance, refuses to play along in the thorny charade that is dining in the obscenely expensive and precious restaurant of the film, Hawthorne, and only she (spoiler alert), the raisonneur Margot/Erin, a high-end escort/prostitute with a taste for cheeseburgers, survives. It’s a wonderful film: smart, gorgeous, shocking, hilarious, and on reflection, quite illuminating. And sooo much fun to talk about with friends!

A note to the interested: Rubin Östlund’s 2017 film The Square, now on Amazon Prime for only 9 more days, is another dark satire of our times: an art museum curator with a life out of control prepares for a controversial new exhibition. Recommended complementary viewing!

Leave a comment