Ever since Daylight Saving Time ended two weeks after I broke my ankle in an earlier careless misstep, I’ve mostly wanted only to eat and to sleep, especially in the mornings when REM time offers the most interesting, sometimes fantastical, sometimes illuminating dreams. I really enjoy what I’ve come to call this recreational sleep, perhaps the best perk of retirement, liberated from the tyrannical alarm clock. I’ve been wondering what cues our local bears, storing calories for hibernation, can take from recent days of 77o temperatures suddenly dipping to more seasonally appropriate lows. Unlike the bears, however, I don’t stop eating after trying out the next interesting recipe from Melissa Clark or Sam Sifton, so currently unable to walk for exercise until my fibula mends, weight gain threatens. I’ve therefore gotten very particular about what and when I eat, and perhaps also benefit from sleeping longer—and two floors away from the kitchen downstairs. Getting up from a warm flannel-sheeted bed always trumps hunger.

Last Sunday I did, however, rouse myself early enough to attend the final performance of Ukrainian-born director Igor Golyak’s hybrid production (simultaneously live and virtual) of The Orchard at the Paramount Theatre in Boston. I saw only the live production, though it was watching Golyak’s 2020 inspired-but-bare-bones virtual production, The State vs. Natasha Banina, that first roused my interest in Golyak, founder and producing artistic director of the Arlekin Players Theatre & the Zero Gravity (zero-G) Virtual Theater Lab. Banina dropped in the very early days of the pandemic and starred Darya Denisova, an actor with the Arlekin Players of Neeham MA and Golyak’s wife; that production’s success excited my anticipation of what Golyak would do with Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. I wasn’t alone in appreciating the necessity-as-the-mother-of-invention creative finesse of Banina: acclaimed in multiple New York Times Critic’s Picks and streamed world-wide, Banina also caught actors Jessica Hecht’s and Mikhail Baryshnikov’s attention, spawning their participation in Golyak’s Chekhov adaptation, which first played off-Broadway at The Baryshnikov Art Center before arriving in Boston.

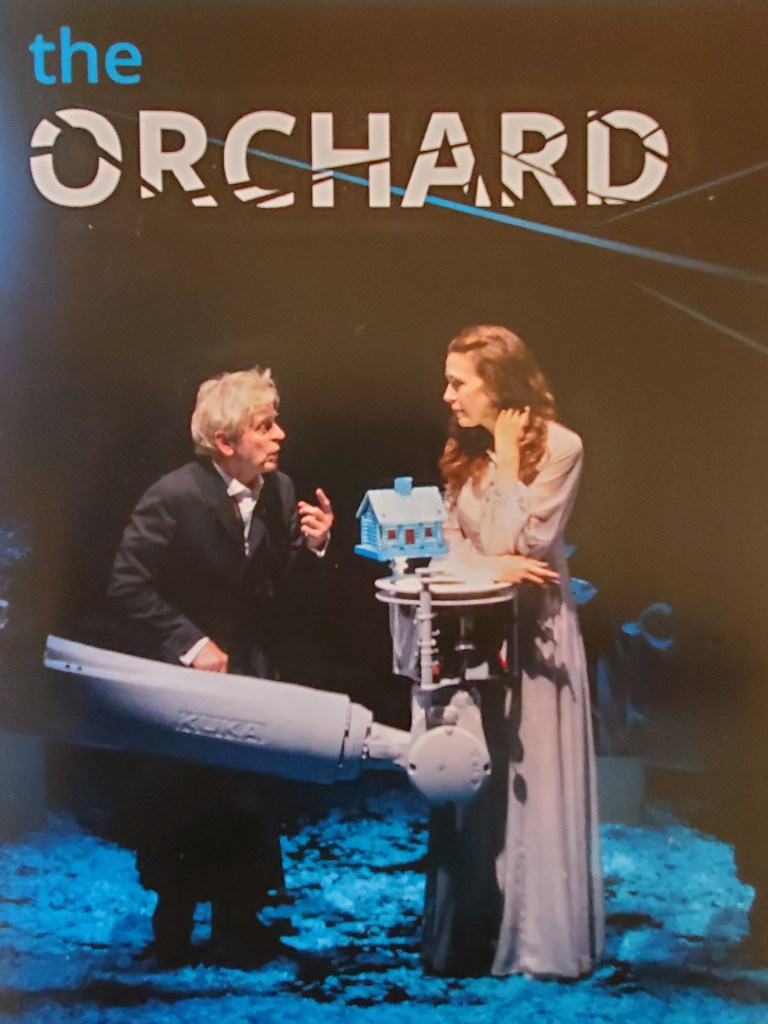

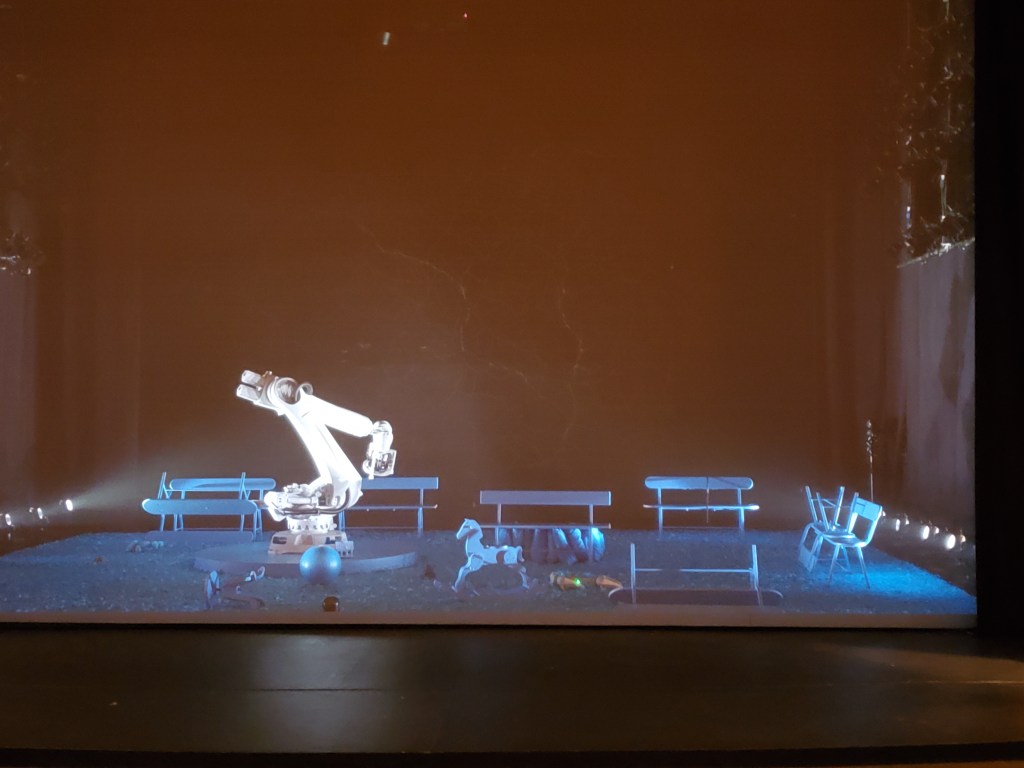

Experiencing Golyak’s production in person felt rather disturbingly akin to my personal Eastern Standard Time recreation: dreaming. Lighting Designer Yuki Nakase Link bathed the action in cold, blue light and projections of swirling precipitation. Falling snow? Cherry blossoms? Both? Neither? You decide. The projections became physical on the stage floor, littered with a snow/blossom cover through which the old servant Firs (Baryshnikov) made his first shuffling entrance. A scrim filled the proscenium arch of the Paramount stage, separating the audience from the live action (except for one alarming entrance and the curtain call), and distancing it in time and space. Projections on the scrim sometimes frustratingly obscured the live action on stage, but perhaps deliberately so, in the way the action of a dream is obscured in waking memory. Sometimes bits of Chekhov’s script, including stage directions, appeared on the scrim, suggesting a script from the turn of the 20th century now hard to follow (and for the audience, hard to see clearly?) well into some future time. The irresponsibly child-like but charming Ranevskaya and her sentimental, loquacious brother Gaev in the script’s opening scene have just returned to their estate after fleeing Paris, and are adrift (literally in drifts of snow/blossoms) in what seems an apocalyptic future. An alienating robotic arm center stage in their former nursery puts us, the audience, in their position, trying to accommodate the discrepancy between a play about a hinge moment in 1904 and characters who cannot adapt to current realities, even as we live through our own era’s estranging novelties and anxiety-provoking changes. Like the feckless siblings clad in Oana Botez’s fur-trimmed quasi-period dress, we in the audience have trouble seeing clearly what is going on as our world becomes increasingly technological and less human. Live actors on stage along with the serviceable (sometimes seemingly sentient) robotic arm seen only through the intervening scrim seem more like apparitions than flesh and blood—like the bending tree in the orchard Ranevskaya initially mistakes for her mother. The setting puts us in the audience in the same liminal position as Chekhov’s characters.

As in a dream, truth in The Orchard is only obliquely suggested: robots replace humans in 2022 just as Lopakhin’s awkward but upwardly mobile capitalism replaced the ruling class of 1904 Russia. The robotic arm, like the robotic dog, even has a discomfiting personality, sometimes photographing the characters, seeming to be listening attentively while recording through the “face” of a ring-lit lens, sometimes serving coffee or a small toy house, the venerable but abandoned estate reduced to plaything. The arm even sweeps the floor, as Firs does. But Firs is mortal; both he and his memories of a past when cherries from the orchard were valuable, like the recipe that once made them profitable, will be forgotten.

The look of this post-apocalyptic dystopia makes us queasy. The robot dog, clearly valued by Charlotta and Firs, who strokes it at one point, is still a robot. Perhaps that’s why my favorite line, a non sequitur from the governess Charlotta, was cut: “My dog also eats nuts!”

Golyak’s adapted script sometimes required translation: Trofimov’s key speech about all Russia being our orchard was delivered in American Sign Language. Some large chunks of dialog, in Russian or French, got no translation at all, especially baffling to those audience members who did not already know the play. Was this a metaphor for how even the characters on stage do not listen with understanding to each other?

Nor was there much comedy to elicit Chekhovian painful laughter. Real menace entered the play as the original script’s passing hiker became in Golyak’s Orchard a soldier who arrived in front of the scrim and close to the audience, his combat uniform and kit as well as his aggressive delivery shockingly contemporary and quite intimidating, evoking both Golyak’s Ukrainian roots (he was born in Kyiv, with, in his words, “an affinity for the Russian culture”) and the experience of the Arlekin players as Russian-speaking immigrants from the former Soviet Union. In Golyak’s own words, quoted in Elisabeth Vincentelli’s NYT review of 3 June 2022: “The idea in The Cherry Orchard is the loss of a world, loss of connection, loss of each other, loss of this family. It’s a story where a human being is forgotten—Firs is forgotten. And right now human being is forgotten.”

Jessica Hecht’s Ranevskaya recalled a Blanche DuBois wanting magic, not reality, longing for connection even as she irresponsibly flees it. As for Mikhail Baryshnikov, critic Laura Collins-Hughes nailed his “ineffable magnetism and captivating grace that have always made him a riveting performer, and that now make him the quietly scene-stealing anchor of this ambitious and cluttered production” (NYT, 16 June 2022). The literal winds of metaphoric change that several times mimetically buffet the actors on stage Baryshnikov as Firs not surprisingly renders with virtuosic moves that make the choreographed action both beautiful and convincingly real, an early coup de théâtre for a production that begins—and movingly ends—with Firs.

Endings have been much in evidence of late. I returned from the The Orchard matinee in Boston to watch later that night another episode of The Crown’s season 5, chronicling the 1990’s increasingly out-of-touch reign of Queen Elizabeth II. In that episode, young William apprises his grandmother the Queen that satellite television could offer her many more viewing choices, including the racing coverage which she of course eagerly embraces. But later, surfing through the hundreds of channels now available to her, each offering something more trashy and banal than the other (one clip is Beavis and Butthead), the Queen herself pronounces that there in Buckingham Palace “even television is a metaphor.”

Certainly the real Queen’s passing this fall has felt like an end time to me. And now at 70, I spend a fair portion of each day fretting about what to do with all the many books two academics can collect over their lifetimes, and the extensive trove of obsolete but carefully preserved technology: vinyl; tapes, both cassettes and VHS; cds; dvds; analog cameras; a multitude of carefully organized and filed 35 mm slides in purpose-built cabinets.

Gaev’s famous apostrophe to the 100-year-old bookcase in the nursery therefore hits rather too close to home—much like grief for the end of the second Elizabethan era, the passing of “the greatest generation,” and the values the Queen herself represented so dutifully throughout her long life.

In the S5 E2 of The Crown, Prince Philip (Jonathan Pryce) tries to comfort a grieving young mother, Penelope Knatchbull, Countess Mountbatten (Natascha McElhone), and speaks of losing his favorite sister to an airplane crash:

“I learnt then what grief was. True grief. How it moves through the body. How it inhabits it. How it becomes part of your skin. Your cells. And it makes a home there. A permanent home. But you learn to live with it. And you will be happy again. Though never in the same way as before. And that’s the point. To keep finding new ways.”

Loss and grief are inevitable. Here’s to finding new ways.

Leave a comment