It is Memorial Day, and as we finish our breakfast on the porch (bagels, cream cheese, smoked salmon, and fruit), the wheeze of bagpipes wafts from downtown, so we hurry to catch the parade in progress.

Enjoying that, and the hipster/Thornton Wilder-esque hybrid downtown, Ann proposes the next diversion, a trip to the Barnes Foundation in downtown Philadelphia.

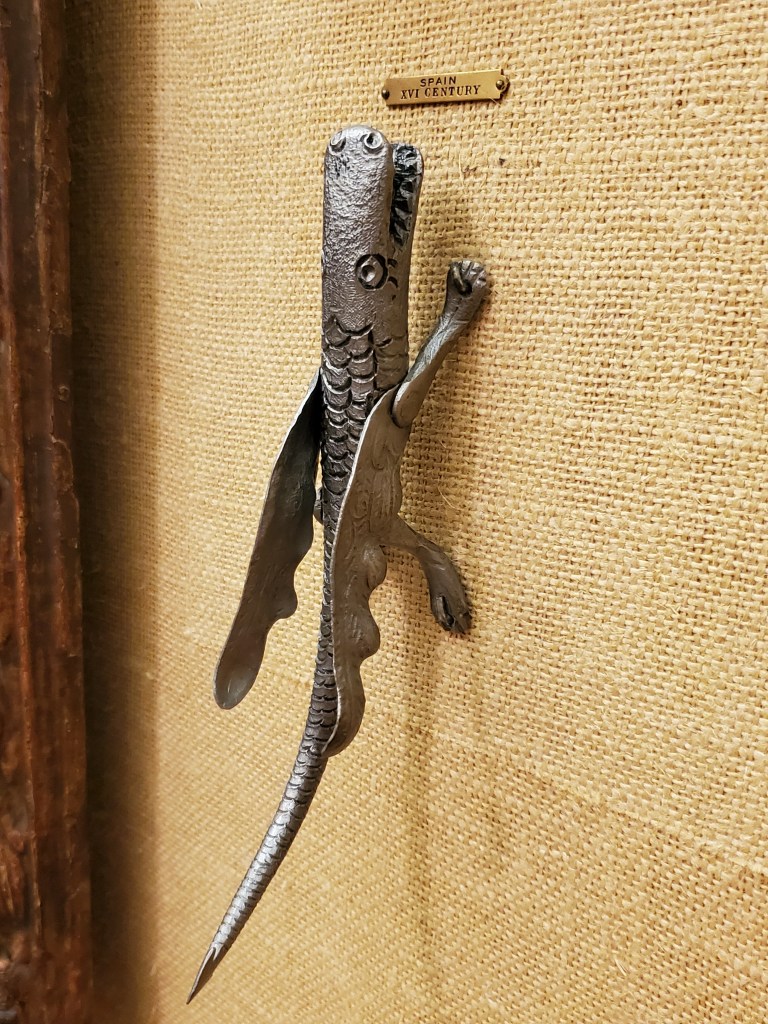

The Barnes houses one of the world’s greatest collections of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Modern Art, all displayed salon style, with Barnes’s curious accompanying collection of hardware, both paintings and fixtures arranged not chronologically but rather paired for the formal correspondences that Barnes believed could teach the uneducated viewer how to look at art.

The Church of Saint-Aspais Seen from the Place de la Préfecture at Melun

The Barnes was founded in 1922 by Albert Coombs Barnes (1872-1951), a chemist and business man who (like his counterpart gilded age pharmacist Edwin Wily Grove in Asheville) made his fortune by co-developing a tonic, Argyrol, an antiseptic silver compound that was used to combat gonorrhea and inflammations of the eye, ear, nose, and throat, and prevented blindness in babies born to syphilitic mothers. He sold his business, the A.C. Barnes Company, just months before the stock market crash of 1929, and devoted himself to philanthropy.

Barnes had begun collecting art as early as 1902, but became a serious collector in 1912, assisted by his Philadelphia Central High School classmate, artist William Glackens. On an art buying trip to Paris, he visited the home of siblings Gertrude and Leo Stein, and purchased his first two paintings by Matisse. Eventually, his collection grew so large that he was housing some of these priceless canvases in his employee’s homes. In 1908, Barnes organized his company as a cooperative, devoting two hours of the work day to seminars for his employees, who read philosophers William James, Georges Santayana, and John Dewey, the latter of whom he had met in a seminar at Colombia University in 1917. Dewey became a close friend and collaborator for more than three decades. Barnes conceived of his Foundation as more school than museum, believing like Dewey (and like the undergraduate research program I used to coordinate) that learning should be experiential. The Foundation classes included experiencing original art works, participating in class discussion, reading about philosophy and the traditions of art, as well as looking objectively at the artists’ use of light, line, color, and space. Barnes believed that students would not only learn about art from these experiences, but that they would also develop their own critical thinking skills, enabling them to become more productive members of a democratic society. He had much in common with Centre College’s now-defunct Humanities Program, it seems. Oh, Mr. Barnes! How much we need your influence in these latter days!

I am made wistful thinking of how far from such democratically inspired philanthropy we have fallen in our era of Zuckerberg and Musk. And as the young docent presents to us her gallery talk, I am reminded of the previous night’s conversation and Barry’s conviction that there is no will that can’t be broken. I learn from Wikipedia that Barnes created detailed terms of operation in an indenture of trust to be honored in perpetuity after his death. These included limiting public admission to two days a week, so the school could use the art collection primarily for student study, and prohibiting the loan of works in the collection, colored reproductions of its works, touring the collection, and presenting touring exhibitions of other art. Matisse is said to have hailed the school as the only sane place in America to view art.

After Barnes’s death, however, decades of legal battles ensued, and (as Barry had said) Barnes’s bequest to Lincoln University, the nation’s first historically black college and university, was broken. Despite legal challenges to moving the Barnes collection from its original home in Merion to Philadelphia, construction for the new building began in fall 2009, and the gorgeous new building opened in May 2012 with galleries designed to replicate the scale, proportion, and configuration of the original galleries in Merion. Truly, I can see why the building won the 2013 AIA Institute Honor Award for Architecture, the 2013 Building Stone Institute Tucker Award, and the Barnes Foundation the 2012 Apollo Award for Museum Opening of the Year.

OLIN, landscape architect

I am certain Barnes would have approved of the scan-and-click technology that dispenses with gallery labels and in their place presents the viewer equipped with a smart phone detailed information about every piece in the collection. There’s so much to see and absorb–a head-exploding trove, in fact. After a couple of hours, Ann and I share tea and a savory brioche in the café, and head for home via the Smith Memorial Arch, a Civil War monument in Fairmount Park with an acoustically remarkable “whispering bench,” conducting the quietest utterance from one end of its curving walls to the other without electronic intervention. We also drive by the original Barnes Foundation in Merion. Now leased along with its adjoining arboretum by Saint Joseph’s University for $100 a year, it retains its original educational purpose.

It’s been a full day. We have another delicious dinner—shrimp and rice, salad, and more blonde brownies—on the porch, and Ann gives me three books to pack up and take home with me the next day, part of the ongoing informal book exchange that has become standard among all my academic friends with TOO MANY BOOKS!

I think Barnes would approve of that, too.

Leave a comment